The enslaved Africans landed in Tobago from the 17th century were brought into a world consumed with the competition between rival European countries...

Vous n'êtes pas connecté

- English

- Français

- عربي

- Español

- Deutsch

- Português

- русский язык

- Català

- Italiano

- Nederlands, Vlaams

- Norsk

- فارسی

- বাংলা

- اردو

- Azərbaycan dili

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Հայերեն

- Ελληνικά

- Bosanski jezik

- українська мова

- Íslenska

- Türkmen, Түркмен

- Türkçe

- Shqip

- Eesti keel

- magyar

- Қазақ тілі

- Kalaallisut ; kalaallit oqaasii

- Lietuvių kalba

- Latviešu valoda

- македонски јазик

- Монгол

- Bahasa Melayu ; بهاس ملايو

- ဗမာစာ

- Slovenščina

- тоҷикӣ ; toğikī ; تاجیکی

- ไทย

- O'zbek ; Ўзбек ; أۇزبېك

- Tiếng Việt

- ភាសាខ្មែរ

- རྫོང་ཁ

- Soomaaliga ; af Soomaali

Rubriques :

Maroc - NEWSDAY.CO.TT - A la Une - 16/Nov 10:29

Maroc - NEWSDAY.CO.TT - A la Une - 16/Nov 10:29

Post-treaty tensions in Tobago

The Treaty of Paris of 1763 might have been a signal for a British sigh of relief over the possession of Tobago. However, the post-treaty reality was no honeymoon for the administration of Tobago: this promised to be a tension-filled era. The French submitted at the conference table during discussions of the island under duress, and the first reality the British administration had to face was that the contest was far from over and France had every intention of continuing the fight for the island. The administration became very security-conscious because of the recognition that British survival depended on effective security arrangements. The administration’s first response was an attempt to increase the resident population with British landowners who would have a vested interest in defending the island against French or other competitors. Their solution was to establish a militia of loyalists to stave off any external attack, as well as internal attack from a resisting enslaved population, whose numbers were increasing with the landing of each slaver. One of the first laws passed was to keep the enslaved under “proper restraints” for the greater security of the property of the island’s inhabitants. But these measures were not enough. There was no significant increase in the white population, and fears that the French would use enslaved resistance as the opportunity to attack. One challenge was the vulnerability posed by the many bays around the island. These, especially Pirates Bay, were hideouts for pirates who attacked trading ships and French privateers who sought to destabilise the island on behalf of France. This was cause for serious concern, since the British administration was anxious to bring the island under quick cultivation, with a British land-owning population in control. But increasing the number of plantations did not mean an increase in the white male presence, for although there were 77 British land purchasers by 1768, only 20 were resident, increasing the number of absentee landowners. The demand for plantation labour spawned increasing slave trading through the many bays which served as ports of entry for the slavers. As result, the enslaved population increased to almost ten times the white population. The security of the bays became a matter of utmost importance. In 1772, the attempt to tighten security was manifested in an act to appoint suitable men to the ranks of colonels, captains and privates, with the challenging responsibility of taking charge of batteries to defend all the bays from interlopers. Given the existing human resources, this was an impossible task, and the problem remained an unresolved but vexing matter. Greater effort was directed to the major shortcoming of the land commissioners, who were responsible for dividing the island into plantation-sized portions of up to 500 acres. The initial plantations abutted each other, creating a virtual plantation fence across the island. The commissioners were so preoccupied with land division that they failed to provide for communication between estates and for cross-island contact. Roads, which did not feature in their plans, were recognised as of critical importance to prevent and counter the security threats. The administrators sought to correct this major omission, dividing the island into parishes and plantations. It was noted that, given the daily increase in the number of plantations, there was a need for public roads across the island. A land tax of six pence per acre was imposed on all landholders to raise funds. Commissioners for public roads were appointed. Landowners were required to provide one enslaved African for every ten they owned, with a male/female balance. Each had to be furnished with a good axe, a cutlass, a hoe and sufficient food and was to be employed on the public roads as long as the commissioners required their services. Owners were paid three shillings per enslaved worker per day from public funds. The first roads were to be in the parishes with the largest estates: St George, St Mary, St Paul, St Andrew, St Patrick and St David. These were called leading roads and led to Scarborough through the parishes to the easternmost boundary of St Paul. Another leading road passed through St Andrew, St Patrick and St David to the easternmost boundary of St David and from Plymouth through St David and St Andrew to Scarborough. These roads were intended to facilitate communication with principal boats and shipping places within the several parishes. Some of any remaining funds was to be spent to encourage settlement in St John, and the rest to be expended as the commissioners warranted. Nothing was to inhibit the road-construction drive. Removing trees, clearing cultivated areas, cutting passes through plantations and excavation for road-construction material were all allowed. Proprietors or their agents were allowed to make roads in any convenient areas or alter roads within their plantations to get to church, market, a convenient harbour or landing place for shipping, and to cut timber and remove soil as necessary. The communication plan was extended into creating round-the-island Great Roads of Communication, which linked settled areas with cross roads through the unsettled areas. A sum of £1,500 was allocated and additional commissioners named for this leg of the project: five in St George, four in St Paul, three for part of St John from the boundaries of St Paul to the west end of Man of War Bay and three for the Great Road of Communication from the west end of Man of War Bay to King Peter’s Bay, for the cross roads from Castara to Fort Granby which needed to be repaired, around the island from Tyrell Bay by Man of War Bay to Bloody Bay and from Castara Bay to King Peter’s Bay to complete the Great Road. This was a great idea and an essential plan way in advance of its time. But it was a long-drawn-out process to deal with a situation which called for immediate attention. Although fear of a French invasion continued to cause tension, the road project was not executed as needed, given the exigencies of the time. During the 1770s, the island was rocked by repeated resistance by enslaved Africans which challenged its military resources, added to security tensions and consumed the attention of plantation owners, on whose support the project relied. In addition to the domestic crisis, the limited number of white men considered qualified for such responsibilities and the multiple responsibilities of those put in charge of operations contributed to the lack of effective action by office-holders. As a result, even the leading roads remained in a state of disrepair, cross-island communication remained an everyday challenge and the island’s defences remained unsatisfactory. Communication with the northern areas continued to plague residents and administrators into the 20th century. Ultimately, it was intelligence of this weakness in its defence which, to the shock of the planting community, allowed France to recapture and occupy Tobago in 1781. The post Post-treaty tensions in Tobago appeared first on Trinidad and Tobago Newsday.

Articles similaires

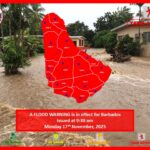

Flash-Flood Warning still in effect across the island

Barbados is again under a flash-flood warning as conditions remain unstable across the country. The Barbados Meteorological Services upgraded the...

NWA working to restore traffic signals in western parishes

The National Works Agency (NWA) is undertaking extensive repairs to its traffic signal infrastructure in the Western parishes of St James, Trelawny,...

Black River: From Gravesend to ghost town to ruin

The parish of St Elizabeth was among 12 Anglican parishes established between 1655 and 1675, named after Elizabeth, Lady Modyford, wife of Governor...

Black River: From Gravesend to ghost town to ruin

The parish of St Elizabeth was among 12 Anglican parishes established between 1655 and 1675, named after Elizabeth, Lady Modyford, wife of Governor...

The social media government

The accusations levelled by Senator Anil Roberts against the family of St Vincent and the Grenadines PM Ralph Gonsalves were not part of any...

The social media government

The accusations levelled by Senator Anil Roberts against the family of St Vincent and the Grenadines PM Ralph Gonsalves were not part of any...

Dennis: PNM will fix Tobago’s poor customer service

PNM Tobago Council political leader Ancil Dennis says poor customer service remains the bane of the island’s tourism sector. In August 2021, during...

Dennis: PNM will fix Tobago’s poor customer service

PNM Tobago Council political leader Ancil Dennis says poor customer service remains the bane of the island’s tourism sector. In August 2021, during...

Realities of revitalisation: Business leaders on way forward with economic blueprint

The government has a grand vision for the future. With high-rise buildings, medical complexes, new roads and waterfront properties, the government in...

Les derniers communiqués

-

Aucun élément